Archive for the ‘middlegame’ Category

300 Most Important Chess Positions

300 Most Important Chess Positions

Study Five a Week to Be a Better Chessplayer

By Thomas Engqvist

Batsford, 2018

ISBN: 9781849945127

Depth is the main aim, but breadth is well served here too.

At heart, the book is made up of 300 positions, most of them taken from master games though some studies and theoretical positions (by Lucena, Philidor, Vancura and others) are put in for good measure.

In Part 1 there are 150 positions touching upon the opening and the middlegame both and arranged into six broad categories: Development of the Pieces, Exchange of Material, Manoeuvring, Pawn-Play and the Centre, Play on the Wings, and what Thomas Engqvist calls Psychological and Pragmatic Moves. This latter category of position touches upon the human aspect of chess, whether it involve taking risks to win, making the most of a duff situation, attempting to keep a lid on potentially chaotic complications. Since chess is closer to a life and death struggle between adversaries rather than an academic debate, all well and to the good.

As for Part 2, can be found a further 150 positions but this time solely devoted to the ending. The positions are ordered by type of ending, according to the pieces or material present: Pawn Endings, Knight Endings, Bishop Endings, Knight and Bishop Endings, Rook Endings and Queen Endings.

It will be noted that the opening and the middlegame are conflated in Part 1, whereas most weight falls on the ending. In part this is because it is often difficult to say precisely when the opening ends and the (early) middlegame begins (perhaps there is need for a tranitional phase?) but it due also to the fact that the ending is the most irrefragable part of the game. Here Engqvist and Capablanca (and me too, for that matter) agree.

Here it seems apposite to note that there is a set of borderline positions which Engqvist, following Glenn Flear, describes as Not Quite an Ending (NQE). For example, positions where one side has King, Queen and Rook v King, Queen and Rook with several pawns present too. These are positions where some threat to the king remains, since Queen and Rook together have clear attacking potential. So both sides need to take care. Probably, it wouldn’t be a good idea to rush forward a pawn with the aim of promoting it (a typical ending plan) if it leaves your king denuded of defensive cover.

Can it be said with certainty that these are really the ‘300 Most Important Chess Positions’? Well, that claim can no doubt be challenged or questioned. But there is no doubt of the significance of these positions and their value as study material.

I was intrigued by Engqvist’s notion that ‘less is more’, in other words that you should limit your study material to these 300 positions only, but study and examine them thoroughly and in depth. And while depth is the primary aim, breadth is well served here too. And there is sufficient variety to cater for players with different styles.

To refresh your understanding of each position, Engqvist recommends scheduled repetition and here modern technology in the form of Mochi or Anki flashcards can come in handy.

I greatly enjoyed playing through the many fascinating and instructive positions in this book. Perhaps the position that I relished most of all was number 205, an ending where Flohr’s two bishops prevailed over Botvinnik’s two knights (each side had an equal number of pawns, though Flohr had something of a space advantage). It was pure class on Flohr’s part and Botvinnik learnt his lesson well, for it was this very ending (Botvinnik with the two bishops this time but a pawn down) that brought him a crucial victory in the 1950 World Chess Championship match versus Bronstein.

A very fine book

The publisher’s description of 300 Most Important Chess Positions can be read here.

The Caro-Kann: The Easy Way

The Caro-Kann: The Easy Way

By Thomas Engqvist

Batsford, 2023

ISBN: 9781849948166

An excellent introduction to the Caro-Kann that gives a sound repertoire for newcomers.

Here Thomas Engqvist provides the reader with a solid, no-nonsense way of meeting 1.e4, based (naturally enough) on the Caro-Kann Defence.

He starts by setting out the historical background behind the opening, reminding us that Horatio Caro and Marcus Kann, its co-inventors (who despite being contemporaries never, as far as I can tell, actually met each other), were strong players in their own right. There is a very pretty win by Kann against Mieses, played at Hamburg in 1885, using the defence, the winning tactic involving a pair of pins and a deadly Zwischenzug. Six of Capablanca’s games are included, though on reflection this really should come as no surprise. Not only was the third world champion an early advocate of the Caro-Kann, his games even now are models of how the middlegames (and indeed endgames) arising from it should be played. Many of them are strategic masterpieces.

A watershed moment for the Caro-Kann occurred when Botvinnik adopted it as black in the 1958 World Chess Championship match versus Smyslov. The great chess scientist demonstrated its worth in that match and in later games and, since then, many world-class, strategically oriented players, notably Petrosian, Karpov, Seirawan, Dreev and, yes, even the great Smyslov himself, have taken it up too.

As for Engqvist’s proposed repertoire, it consists of solid, sound and relatively straightforward lines, all of them designed to get you up and running and playing the Caro-Kann in as little time as possible. Wherever possible, complications are eschewed and so the suggested moves and systems, while decent remedies, may not strictly speaking be the best (whatever that means in this context; in opening theory ‘best’ often just passes for what is fashionable and fashions change). The book is a traditional opening monograph in that the variations are set out in a branch-like form, yet each chapter also contains at least one model game. There are 48 such model games altogether, Engqvist playing the Caro-Kann in eight of them: the author walks the walk as well as talking the talk. His annotations involve lots of elucidation and exlanation, yet there is deep analysis in the notes too; and even the odd innovation.

Most attention is focussed on the Classical Variation (1.e4 c6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 or Nd2 dxe4 4.Nxe4), where Engqvist plumbs for Capablanca’s tried and trusted 4…Bf5, and the Advance Variation (3.e5), where he recommends 3…Bf5. It is a definite advantage of the Caro-Kann, over the French Defence say, that black can quickly bring his queen’s bishop onto a good diagonal. Indeed, the …Bf5 is so strongly posted that white will often hurry to exchange it with Bd3. After 3.e5 Bf5 white has many moves, ten options being given here, but 4.Nc3 is the sharpest and it serves also as a reminder (to me anyway!) that, whatever the opening, you cannot avoid sharp positions altogether, nor situations that you might not be altogether happy with.

Later chapters cover all white’s other variations and systems, though not in as a great a detail. So we have the Panov Attack (3.exd5 cxd5 4.c4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 and now 6.Bg5 e6 or 6.Nf3 Bg4), the Exchange Variation (4.Bd3), the Tartakower-Smyslov Variation, which I still think of as the Fantasy Variation (3.f3), the Steiner System (2.c4), the Two Knights Variation, a one time Fischer’s favourite (2.Nc3 d5 3.Nf3), and what is here called the Breyer Variation (2.d3). I liked all of Engqvist’s suggested lines, except for one. In the Steiner System he gives 2.c4 d5 3.exd5 cxd5 4.cxd5 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nxd5 6.Nf3 Nc6 7.Bb5 and now 7…Nxc3 as the main move, whereas 7…e6 (which he says is likely best) would fit as well into his repertoire, in my view. And 7…e6 is not unduly complicated, no more so than 7…Nxc3 anyway.

However, dont let this negligible niggle unduly discourage you. Thomas Engqvist has written an excellent book, a very worthwhile introduction to the Caro-Kann that, while doing justice to its strategic complexity, provides a sound repertoire for newcomers.

The publisher’s description of The Caro-Kann: The Easy Way can be read here.

Chess Lessons from a Champion Coach

Chess Lessons from a Champion Coach

By Thomas Engqvist

Batsford, 2023

ISBN: 9781849948043

Chess strategy as seen in the games of the greatest players.

In this highly instructive book Thomas Engqvist aims to set out the key principles and concepts of chess strategy, as well as to chart how chess thinking has evolved over the course of five centuries. He does this by examining the games of great players, those who were the strongest of their day. The first chapter looks at the play of Ruy Lopez (though here only a few game fragments are known, apparently), whilst the last chapter showcases the sublime talents of Magnus Carlsen, former world champion and long time world number 1 (here two games are given); the intervening chapters look at 30 other players in the meantime. While I might quibble with a few of the inclusions (there is a chapter, ‘Efim Bogoljubow: The Optimistic Player’, for example, where I might have had Bent Larsen in that role), he makes a pretty good case for each one.

As you would likely expect, more attention is heaped on the absolute best players, the veritable GOATs, and in this you would be proved right most of the time. To make one comparison: Paul Morphy, the great American genius, is alloted 5 pages, while the greatest American genius, Bobby Fischer, gets 13 pages, over twice as many. There is, however, one notable exception to this. By far the greatest amount of attention is paid to Wilhelm Steinitz (29 pages, in fact), this substantial chapter being taken up with a presentation and explanation of his strategic principles, as well as including six of his most important games. He was, of course, a pivotal thinker, as well as being world champion for a long period. By way of contrast, Nimzowitsch, another profound strategic thinker, receives a mere 5 pages.

It is a terrific read, this book, a history of chess strategy told through the games of its greatest players, each chapter being a kind of portrait in a gallery. Engqvist is in his element as he explains the ideas behind the moves, providing deep analysis at each critical juncture, as and where necessary . His detailed annotations are always enlightening. Indeed, they are the main virtue of the book, which can be read as an anthology of interesting and historically significant games.

One notion that struck me as I read the book was that certain practical players’ games exemplify chess strategy (and even particular chess concepts) better than the player, a strategic thinker, who had originated the concept. Rubinstein’s games, for example, are a pure distillation of Steinitz’s theories. Whereas Petrosian’s games give us a profound understanding of how prophylaxis can be used to not only limit the opponent’s aggression, but to leverage control of of the play. Much more so than Nimzowitsch’s own games and writngs, wonderful though they are.

There are, in my view, three or, better, four main classes of player, when it comes to discussing strategic principles and concepts.

First, there are those players who were pioneering thinkers too. Think Steinitz, Nimzowitsch, Philidor.

Second, there are the players who as writers systematised current knowledge, perhaps adding something of their own. Among this number I would include Lasker, Tarrasch and Euwe.

Third, the players who never put forth a grand theory or presented an overarching, general scheme but whose ideas and understanding and approach can be gleaned from the annotations to their own games: Alekhine, Botvinnik, Tal.

Fourth and finally, the players who have left us only their games and sporadic annotations. Here I think of Morphy, Petrosian and Spassky.

Of course, there are players who cut across these categories too. Fischer annotated 60 of his games, but they were not his best games and, anyway, it is hardly comprehensive. To understand Fischer’s play we must turn to others +: Agur, Soltis, Timman, etc.

Chess Lessons from a Champion Coach is a well structured, well thought out work which will surely increase your understanding of chess strategy; and it will allow you to set those strategic ideas in their proper historical context.

The publisher’s description of Chess Lessons from a Champion Coach can be read here.

Chess Lessons from a Champion Coach

Chess Lessons from a Champion Coach

By Thomas Engqvist

Batsford, 2023

ISBN: 9781849948043

Chess strategy as seen in the games of the greatest players.

In this highly instructive book Thomas Engqvist aims to set out the key principles and concepts of chess strategy, as well as to chart how chess thinking has evolved over the course of five centuries. He does this by examining the games of great players, those who were the strongest of their day. The first chapter looks at the play of Ruy Lopez (though here only a few game fragments are known, apparently), whilst the last chapter showcases the sublime talents of Magnus Carlsen, former world champion and long time world number 1 (here two games are given); the intervening chapters look at 30 other players in the meantime. While I might quibble with a few of the inclusions (there is a chapter, ‘Efim Bogoljubow: The Optimistic Player’, for example, where I might have had Bent Larsen in that role), he makes a pretty good case for each one.

As you would likely expect, more attention is heaped on the absolute best players, the veritable GOATs, and in this you would be proved right most of the time. To make one comparison: Paul Morphy, the great American genius, is alloted 5 pages, while the greatest American genius, Bobby Fischer, gets 13 pages, over twice as many. There is, however, one notable exception to this. By far the greatest amount of attention is paid to Wilhelm Steinitz (29 pages, in fact), this substantial chapter being taken up with a presentation and explanation of his strategic principles, as well as including six of his most important games. He was, of course, a pivotal thinker, as well as being world champion for a long period. By way of contrast, Nimzowitsch, another profound strategic thinker, receives a mere 5 pages.

It is a terrific read, this book, a history of chess strategy told through the games of its greatest players, each chapter being a kind of portrait in a gallery. Engqvist is in his element as he explains the ideas behind the moves, providing deep analysis at each critical juncture, as and where necessary . His detailed annotations are always enlightening. Indeed, they are the main virtue of the book, which can be read as an anthology of interesting and historically significant games.

One notion that struck me as I read the book was that certain practical players’ games exemplify chess strategy (and even particular chess concepts) better than the player, a strategic thinker, who had originated the concept. Rubinstein’s games, for example, are a pure distillation of Steinitz’s theories. Whereas Petrosian’s games give us a profound understanding of how prophylaxis can be used to not only limit the opponent’s aggression, but to leverage control of of the play. Much more so than Nimzowitsch’s own games and writngs, wonderful though they are.

There are, in my view, three or, better, four main classes of player, when it comes to discussing strategic principles and concepts.

First, there are those players who were pioneering thinkers too. Think Steinitz, Nimzowitsch, Philidor.

Second, there are the players who as writers systematised current knowledge, perhaps adding something of their own. Among this number I would include Lasker, Tarrasch and Euwe.

Third, the players who never put forth a grand theory or presented an overarching, general scheme but whose ideas and understanding and approach can be gleaned from the annotations to their own games: Alekhine, Botvinnik, Tal.

Fourth and finally, the players who have left us only their games and sporadic annotations. Here I think of Morphy, Petrosian and Spassky.

Of course, there are players who cut across these categories too. Fischer annotated 60 of his games, but they were not his best games and, anyway, it is hardly comprehensive. To understand Fischer’s play we must turn to others: Agur, Soltis, Timman, etc.

Chess Lessons from a Champion Coach is a well structured, well thought out work which will surely increase your understanding of chess strategy; and it will allow you to set those strategic ideas in their proper historical context.

The publisher’s description of Chess Lessons from a Champion Coach can be read here.

The Power of Tactics, Volume 3

The Power of Tactics, Volume 3: Calculate like Champions

By Adrian Mikhalchishin and Tadej Sakelsek

Chess Evolution, 2020

ISBN: 9786155793233

A deep dive into tactics that will leave you refreshed and ready for battle.

There are, taken altogether, 600 tactical exercises in this book, alongside very detailed and informative solutions for each exercise. For most positions (though not all: see below) you are told only what side is to play (White or Black) and what the outcome should be after best play (which might be a winning advantage for White, a bog-standard advantage for Black, or even equality). If you are curious about who the players were, and where and when the game was played (all the positions derive from actual tournament and match games), the solutions tell you this, at the end, .

The exercises are arranged into 10 sections, and often in quite an imaginative and interesting way. To start with there’s ‘Simple Solutions’, which has 40 positions where the tactic is relatively straightforward, though even here it can be well camouflaged. ‘Win the Material’ is likely self-explanatory: the positions in this section usually feature a double attack of some sort (a fork or skewer, perhaps), although in some positions a threat of checkmate is present too.

Next, there is an intriguing section entitled ‘Tactics According to Smyslov’, which is based on the seventh World Champion’s view that most tactics involve one or more of just four components: check, pin, double attack and unprotected pieces. Of these, I would say that the unusual inclusion of ‘check’ is worth reflecting upon. A check is a kind of accelerant, it escalates the play, and it depends on an exposed King (a target akin to an unprotected piece). Since your opponent’s response to a check is limited (the King must be made safe) it can give you, in a sense, two moves in sequence. I don’t doubt that these were the tactical elements that came up most in Smyslov games, and are reflective of his experience. It is worth bearing in mind, however, that he was a supremely gifted positional player and not an all-out attacker.

Combinations don’t always arise logically from positional play, as Reti once famously asserted, but may come about through accident, oversight or happenstance. Purdy made this point somewhere, I believe, in one of his many instructive articles. Anyway, in the section ‘Unexpected Opportunity’ we have 36 positions where the sad scenario (for one player only, to be sure: luck favours the other) of a rupture in the logical flow of play occurs.

Our next section, ‘Make a Choice’, asks us to choose between usually two yet sometimes three or occasionally more moves. It is a multiple choice section (of the form ‘X or Y?’) and contains a whopping 60 positions. With ‘Evaluate if the Move is Possible’ you are presented with a candidate move and asked whether it can be made to work (here we have questions of the form ‘Can White play Bxh7+?’). Generally, the move is desirable if you can pull it off, yet it may be a treacherous temptation.

Other sections include ‘Answer the Question’ (which is what it says on the tin, though any answer needs to be supported by analysis) and ‘Play Better than Champions’, where you are invited to improve on the move of a great player (you might be asked: ‘X played Y. What better move did he overlook?’). As for ‘Complicated Calculation’, here the onus is above all on accuracy and comprehensive coverage of every possible defence; but imagination is required too.

Finally, the last section has loads of practical exercises (192 to be precise) with a wide variety of tactical themes present in the play.

There is some overlap here in that certain positions could, you feel, have fitted in other than their designated section. But overall these positions were astutely selected. I found them testing and teasing, instructive and inspiring, entertaining and exciting. This is a book which you can dive into for pearls, emerging refreshed and ready for battle.

The publisher’s description of The Power of Tactics, Volume 3: Calculate like Champions can be read here.

The Chessmaster Checklist

The Chessmaster Checklist

By Andrew Soltis

Batsford, 2021

ISBN: 9781849947145

Here be wisdom.

Andrew Soltis’s very helpful book touches on topics previously covered by Alexander Kotov in Think Like a Grandmaster, Simon Webb in Chess for Tigers and John Nunn in Secrets of Practical Chess. His approach, however, is very different to those three books. He sets out 10 questions that you should ask yourself (really should ask yourself!) before you make a move, questions such as ‘What does he threaten?’ and ‘What is wrong with his move?’ and ‘What does he want?’ (And, just in case you are wondering, the answer is Yes: where a personal pronoun is used in a question, it is invariably the male pronoun.) These questions, taken together, make up ‘the chessmaster checklist’ of the book’s title. Chapters 1-8 cover questions 1-8, naturally enough, while questions 9 and 10 are crammed into chapter 9. I should add, also, that a few stray, supplementary questions edge their way into the text too.

To be sure, not all masters, grandmasters or even super-grandmasters will ask these questions explicitly during play (though, who knows, they might) but their established patterns of thought, their cognitive routines, will undoubtedly be guided by them. On one level, the very basic question ‘What does he threaten?’ (and note that there may be more than one threat) is a way of avoiding blunders, but it is also a way of kick-starting your sense of danger, increasing your level of alertness, ensuring you are battle-ready for the challenges in front of you and those that will surely lie ahead. Other questions, such as ‘What is his weakest point?’ and ‘How can I improve my pieces?’ act as guides to strategy, serving to orientate you toward the most relevant features of position, the appropriate and apt plan.

Perhaps the best way to describe the book is to say that it is full of a series of episodic reflections, with each position (there are a plethora of diagrams throughout, incidentally, and the book can be easily read without setting up pieces on a board) being a potent vignette, astutely chosen to illustrate the points that Soltis wishes to make. Sensible advice and the odd startling insight (to accompany the odd startling move) spring forth, as he elaborates on what each question is meant to accomplish. There is a‘What to Remember’ section to draw each chapter to a close, this being an outline summary of his key points, a list of take-home messages. And there is a quiz too, consisting of about 10-15 puzzle positions at the end.

I found the quiz positions entertaining and challenging overall, though some solutions were, or seemed to be, perfunctory. In position 87, for example, the best move (or so it seems) is 1.g4, with the threat of 2.Qg7+Ke6 (2…Ke8 3.Qg8#) 3.Rxd6+ Rxd6 4.Rxd6+ Nxd6 5.Qe7#. Black could defend against this by playing 1…Nxc4 but then 2.Qg7+Ke6 3.Qh6+ Kf7 4.Qxh7+ Kf8 5.Qh8+ Kf7 6.Qg7+ Ke6 7.Qg6# follows (remember, the opponent may have more than one threat). White should, therefore, throw one more attacking piece into the fray (the answer to Soltis’s question), but it is the g-pawn not the foremost rook on the d-file. Yet the move 1.g4, supporting the knight on f5 and so giving the white queen freedom to roam, is not mentioned at all.

I got a real kick out of The Chessmaster Checklist, finding it an immersive and instructive read. Mainly, I think, because it is both focussed (on the 10 questions themselves) and wide-ranging (since each question raises contrasting issues, relates to different aspects of chess), so allowing to Soltis opportunity to shine: he is an erudite as well as an engaging writer. Furthermore, the book is both practical and educational, down to earth and informative: study it well and both your playing strength and chess understanding will burgeon. For myself, I learned a lot, much of it fascinating. Take Purdy’s Protection Principle, for example. I had never heard of it before but, on reading Soltis’s explanation of it here, it strikes me as being not only true but paradoxical and profound. Protect your pieces, the principle says, but in doing so take care that you don’t create dependence and vulnerable relationships. A startling insight but sensible advice. And easier said than done!

The Chessmaster Checklist is a fine book. Here be wisdom.

The publisher’s description of The Chessmaster Checklist can be read here.

300 Most Important Chess Exercises

300 Most Important Chess Exercises

Study Five a Week to Be a Better Chessplayer

By Thomas Engqvist

Batsford, 2022

ISBN: 9781849947510

300 MICE, it sounds like a fairy-tale with a cautionary morale.

Yet it is, in truth, a robust work that’s well put together. There are four parts to this challenging workbook, with 75 exercises allotted to each part (that is 4 x 75 = 300). Exactly half of the exercises are concerned with the opening and middle-game, and they are presented in Parts 1 and 2, leaving those exercises whose provenance is the endgame to lounge in Parts 3 and 4.

Not all of the exercises are tactical in nature and, anyway, it is rather a nebulous category, since there is often a wider point (a plan, a strategy) to any tactical operation; and, conversely, many strategic goals can be (indeed frequently are) facilitated by the odd tactical flourish. Why, just think of Capablanca’s notion of the ‘small combination’ that somehow fortuitously appears when you are carrying out the correct plan.

In the exercise sections of the book, you are simply presented with a diagram (there are 4-6 to a page) and told which side, white or black, is to move: nothing more. Thomas Engqvist has chosen to set out the positions like this because he wants the exercises to be akin to, and as far as possible identical to, a competitive game played in a match or tournament. It makes perfect sense to me, I have to say, and for a very definite reason: Ulric Neisser’s long forgotten phrase ‘ecological validity’ leapt into my head. Engqvist’s explanation of the rationale behind his methodology references Botvinnik, but I think that Neisser would approve of it as well.

He recommends also, and this I found absolutely fascinating, that you should attempt to analyse each position periodically, looking ever deeper each time, until you have fully assimilated the ideas (whether strategic, positional or tactical) contained in each one. Because the positions have been so astutely chosen, it makes a lot of sense to do this; though I would range widely as well, mind, since it is always good to keep your oar in.

The solutions are very detailed and informative, perhaps in part as recompense for the necessary sparseness of presentation when it comes to the exercises, and it was to my mind significant that they were at their most comprehensive when the exercises were not tactical. 108 and 125 pages are given over to the solutions to the exercises in parts 1 and 3, whereas parts 2 and 4 (the ‘tactics’ exercises) warrant only 59 and 55 pages respectively. That is because, when it comes to strategy, you have to convey not only what the correct line of play is, but how and why it works. Also, how it can be applied in other, similar situations.

This book is rich in ideas, and it will reward tenfold the effort that you put into it. Of course, solving these exercises is not entirely like playing a tournament game. For here you know, starters, that there is an idea to find and, moreover, that it is ‘important’, and so significant (in other words, an idea that wins or forces a draw from an unfavourable position). But it comes as darn close to simulating actual play as a book can. And the effort to hit upon the best move, to delve into the depths of a position, will repay dividends later.

Those hidden tactical tricks, that technique for winning a pawn ending, this curious knight manoeuvre; the storehouse of stratagems contained herein; can be turned to good use in your own games. You acquire an arsenal of weapons and become a more formidable player.

All told, an excellent book.

The publisher’s description of 300 Most Important Chess Exercises can be read here.

The Best Combinations of the World Champions, Volume 2

The Best Combinations of the World Champions

Volume 2: From Petrosian to Carlsen

By Karsten Müller and Jerzy Konikowski

Joachim Beyer Verlag, 2022

ISBN: 9783959209960

A welcome second helping.

This book, like the earlier volume, is an anthology of combinations taken from the games of players who have worn the highest crown. It also serves as a workbook of tactical puzzles.

There are, in this second volume, chapters devoted to all the world champions of the past 60 years: Petrosian, Spassky, Fischer, Karpov, Kasparov, Kramnik, Anand and the current incumbent (though not for long) Magnus Carlsen.

Despite their considerable difference in style and approach to chess – contrast, for example, Kasparov’s ultra-aggressive power play with Petrosian’s safety first policy – all these champions were skilled tacticians. And a facility for combinative play was integral to their success. In Petrosian’s case, his tactical skill likely had an added benefit: he could sniff out possible combinations for his opponent, and snuff them out before they could come about in reality. In his prime, Petrosian acted as a poacher turned gamekeeper.

What is most fascinating, in fact, is seeing how combinations arise in each of these players’ games. Spassky and Kasparov were aggressors, so tactics were meat and drink to them; combinations appear as sparks flying off the wheel of a speeding car; sharp play, a haughty initiative, brings them into being. Look at Karpov, though, and it is a completely different story. There the tactics are subordinate to strategy; they are a way of implementing a plan, or getting it to work, or defusing an opponent’s counterplay. While Fischer’s combinations (and, to a large extent, Kramnik’s too) have an air of inevitability about them, they are the logical outcome of precise positional play. And so you could go on.

The chapters highlight a particular characteristic of each champion’s play (exchange sacrifices when it comes to Petrosian, initiative and attacking play for Spassky, dominance and restraining strategy in the case of Carlsen) and they include special exercises showing them in action. Many classic games (or rather game fragments) are here. There is even the odd twenty first century classic, such as Carlsen’s Qh6+ against Karjakin in the final game from the match played at New York 2016; a victory that meant that Carlsen retained the world championship. Yet there are also a goodly proportion of less familiar but still precious gems.

It is interesting, as well, to look at those situations where a world champion embarked on a combination that was messy or unclear, because it seemed like the best option available. Some of these positions are like that. And a few positions even feature swindles; the combination here being a desperate last try to save a lost position. That is OK, we can admit that it happens in a chess game, notwithstanding that the player may be a world champion. We can talk about it, really, we can. There is no shame, or not much anyway.

Combinations and sacrifices are beautiful, but are they necessary? Recently, Carlsen wrote a course called ‘Attacking without Sacrificing’, an intriguing title and, on the surface at least, one that makes a lot of sense. Attacks succeed (as Steinitz said) because the attacker has superiority in force. Why, therefore, should you sacrifice, voluntarily weaken your army, by giving up pieces? Doesn’t sacrificing mean that your attack is less likely to succeed?

In actual practice, mind, sacrifices occur; and they are effective. Why is this so? Well, because a sacrifice is a violent act. Usually, it is a move that involves a capture, or it has the effect of opening up a line of attack. You might think of it as an assault that draws blood, or that shreds a protective armour prior to a fatal lunge.

Within the pages of the book, there are photos of each player. Spassky looks by far the nicest man, whereas a middle-aged Fischer seems injured and haunted. Carlsen is serious and brooding, Anand is lost in thought, preoccupied with how to escape from a concealed labyrinth. Kasparov surveys the chessboard like a belligerent emperor.

I got a lot of pleasure and profit out of this book, and I relished volume 1 too, come to that. For along with the resplendent, informative snapshots of each and every world champion, there were beautiful combinations to discover, and difficult (and not so difficult) exercises that served to strengthen and sharpen my tactical vision. To be clear, there are about 300 tactical puzzles in total. Of these, 64 are ‘special exercises’ where the combinations align with a specific theme.

The publisher’s description of The Best Combinations of the World Champions, Volume 2: From Petrosian to Carlsen is here.

Fabiano Caruana: 60 Memorable Games

Fabiano Caruana: 60 Memorable Games

By Andrew Soltis

Batsford, 2022

ISBN: 9781849947213

Now it is Fabiano Caruana’s turn.

Fischer began it, you could say, with his classic games collection, My 60 Memorable Games, which came out in 1969 or so. When Andrew Soltis reprised this title (or the bulk of it anyway) by writing Magnus Carlsen: 60 Memorable Games a couple of years ago, well, it seemed at most a cute conceit, a witty one-off. But the current collection of Caruana’s games somehow leads you to suspect that we are merely at the start of a series, and that this is a publishing enterprise bent on world domination. Surely what we have here is only the second of many volumes to come, each one focussing on an elite player?

The book has the same format as the Carlsen volume, beginning with a portrait of Caruana as a player, examining his style and approach to chess. This is then followed by 60 deeply annotated games, played between 2002 and 2021, so covering a period of about two decades. Caruana has been around for a surprisingly long time. These games chart his development (the first game was played when Caruana was just 9 years old) and the best of them, those played when he became an established member of the world’s elite, are gorgeous, volatile beasts full of gory highlights and edgily hoary incidents.

In the introduction, Soltis makes the claim that Caruana’s career reads like a Hollywood script. Well, sort of, but it is hardly a tale of rags to riches. His family was well-to-do and supportive of his passion for chess, and he has had top coaches helping him from an early age. Unlike children from a humbler background, he could afford to fail in tournaments sometimes, since his parents were always able and willing to pay the entry fee for the next one. He has had many privileges and advantages, then, but to be fair to Caruana, he has made the most of them.

It is noteworthy that all his coaches attest to his strong work ethic, his great powers of concentration at the board and his strong, resilient nerves in critical competitive situations. A brilliant calculator, he is at his deadliest when he has the initiative and can create meaningful threats, as shown in many games here, notably game 52, a victory over Anand. Another of Caruana’s strengths is his deep opening preparation (that strong work ethic motoring into overdrive), evidenced here by game 59 and the astounding move 18.Bc4! as played against MVL in a crazy, complicated alleyway of the Poisoned Pawn. This was a game played at the Candidates tournament held at Ekaterinburg in 2021, and I vividly remember watching it live over the web, not quite understanding what was going on.

Several games have spectacular finishes, not least numbers 24 and 32. The former, played against Ponomariev, was a hard fought slugfest culminating in a spectacular, tactical fireworks show and an elegant checkmate. Whilst, against Ivanchuk (game 20), Caruana played an exchange sacrifice that gave him long term positional pressure (I was reminded of a fair few of Ulf Andersson’s games), gradually outplaying the unique Ukrainian genius. I enjoyed this game very much because I felt it showed a different side to Caruana’s play.

If I had to venture a generalisation, I would say that most of these games are complicated affairs where accurate calculation and evaluation are the main skills required, along with nerves of iron (then again, am I not simply describing modern chess?). Caruana has these qualities in spades, and so he prevails most of the time. It was thought provoking, incidentally, to read that early on Karpov characterised Caruana as a product of the Soviet school (and it is true that some of his coaches hailed from the Soviet Union), for if I had to compare him to a great player of the past it would probably be Geller, a Soviet great (who once defeated Karpov himself in a spectacular game).

There is a lot to ponder and much to relish in this excellent book. Soltis has long been a fine guide to the opaque paradoxes and anomalous beauty of modern chess, and in this stellar games collection he is on song again. The words ‘instructive’ and ‘entertaining’, while accurate enough, don’t really do justice to his superlative annotations. At the close I had one question. Who will be the subject of the next volume in this series?

The publisher’s description of Fabiano Caruana: 60 Memorable Games can be read here.

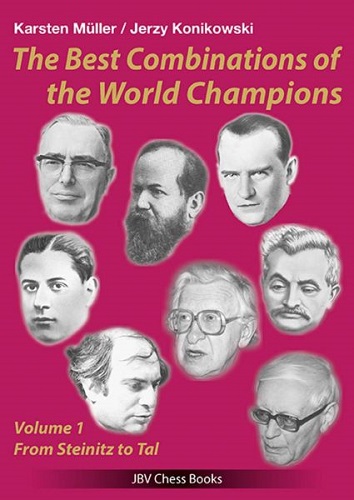

The Best Combinations of the World Champions, Volume 1

The Best Combinations of the World Champions

Volume 1: From Steinitz to Tal

By Karsten Müller and Jerzy Konikowski

Joachim Beyer Verlag, 2022

ISBN: 9783959209953

Only the finest combinations.

This enjoyable book features the best combinations of some of the best chess players who have ever lived. The first eight official world champions are included (so we have Steinitz, Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Euwe, Botvinnik, Smyslov and Tal), with each being allocated a chapter. Unfortunately there is no space for, let’s say, Anderssen or Morphy – both had an eagle eye when it came to combinations – on the grounds that each was at one time the best player in the world. Those are the rules.

Each chapter begins with a summary of the player’s career, followed usually by a couple of annotated games (sometimes a game fragment or position is discussed) showing their tactical prowess. Then a characteristic aspect of their play is dwelt upon: with Steinitz it is his belief in the strong king, with Capablanca it’s his penchant for those ‘small combinations’, with Euwe (interestingly) it is the prevalence in his games of what the authors call ‘dynamic transformations’. Finally, there are 28 tactical puzzles to solve, with the positions naturally being taken from each world champion’s games. Four of these positions are ‘special exercises’, in that you must both find the hidden combination and answer a specific question.

While it is clear that all these players were adept at tactics, combinations occurred at different moments in their games, and for different reasons. For most (but perhaps in particular Capablanca, Botvinnik and Smyslov), a combination occurred as the culmination of previous fine positional play, and signified the triumph of their strategy. Whereas for others (and here I am thinking primarily of Alekhine and Tal) combinations were integral to the cut and thrust of their play. Euwe is a curious case, and comes somewhere in between. Often underrated because he was never a professional player, nor world champion for very long, he is still unappreciated. Yet as a player he was opportunistic and flexible, and could calculate and evaluate positions accurately, so he would play moves and discover combinations that a pure strategist would tend to dismiss out of hand.

The authors introduce a fourfold typology of chessplayers (they are activists, theorists, reflectors or pragmatists) then go on to describe Tal as a ‘hyperactivist’, meaning that his style was strongly tactical and risky. That was certainly true of Tal when he became world champion (which was at a much younger age than the others), but his style changed and matured over time. And he was never as one dimensional a player as he is often made out to be. It seems to me that Alekhine could equally be called a ‘hyperactivist’, though I’d probably reject it in his case as well.

An unusual feature of the book, which worked well, is that each diagram has a QR code. When you read the QR code with your phone, you are taken to a chessbase webpage with the position; and you can see the game continuation and analysis as well. So read the code only after you solve the position first!

This is a fine book, chockfull of fine combinations (some will be familiar but not all), and by working through the exercises you will undoubtedly improve your tactical skill. You will also learn something of the lives and careers of the world champions, which is all part of a liberal chess education. Note, though, that while it is wonderful to have the combinations (spectacular and stellar as they often are) all in one place, the players’ games (at times plodding and earth-bound) should ideally be studied in full.

The publisher’s description of The Best Combinations of the World Champions, Volume 1: From Steinitz to Tal is here.